History of the Clock House site in the Broadway

The wide space at the centre of the Broadway has long been the site of a building or monument. On the 18th century Willis map, a small square building is shown - possibly originally built as a wayside chapel, later becoming residential, as the name ‘Chapel Houses’ suggests.

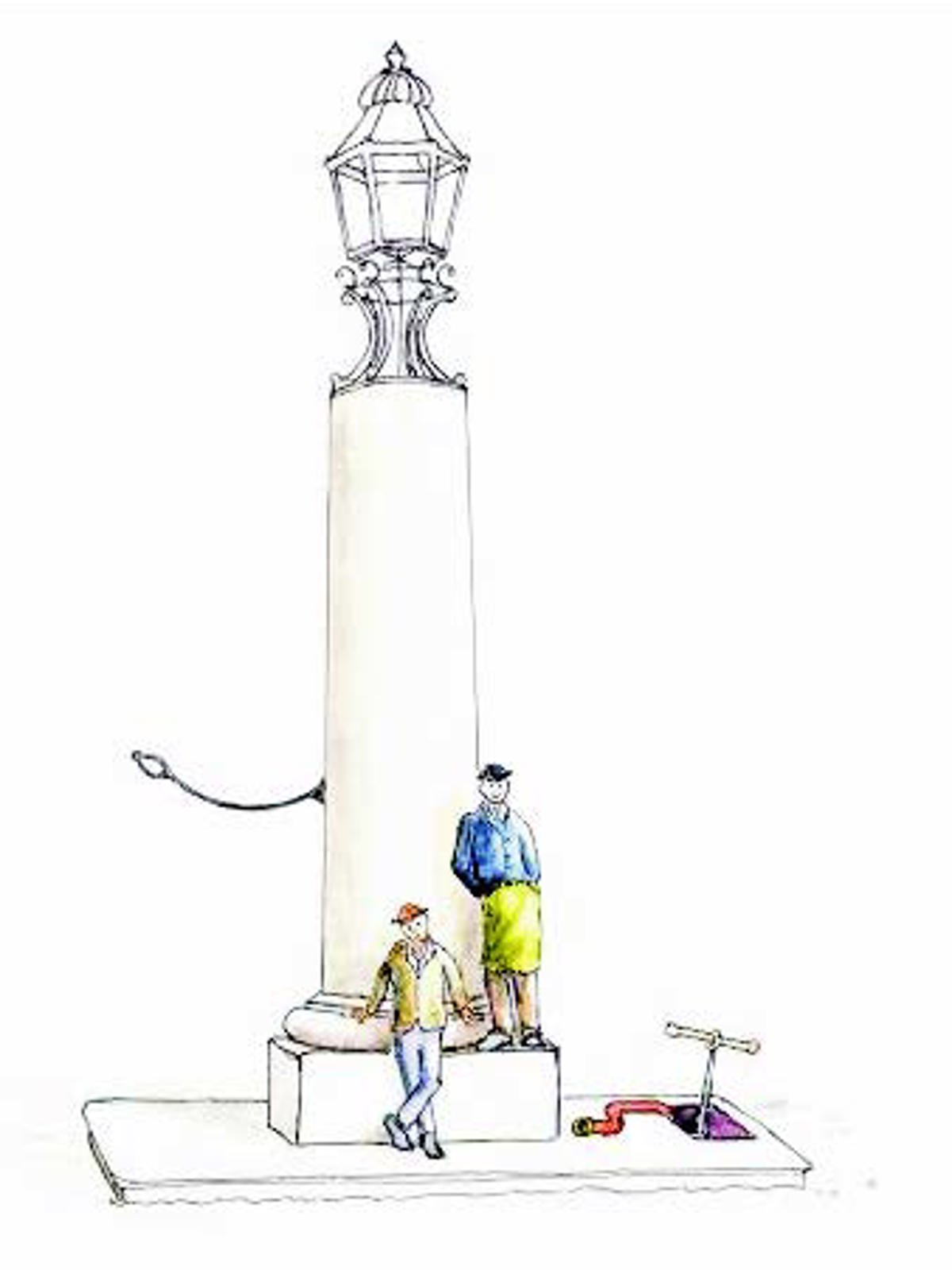

The Speenhamland Lamp 1828-1888

In 1828, at the height of the coaching trade for which Speenhamland was so famous, an impressive gas light appeared on the site. A local businessman, Fredrick Page, of Goldwell House and Chairman of the Kennet and Avon Canal, donated a stone obelisk from his quarry near Bath. The elegant gas lantern for the top (one of the earliest streetlights in Newbury) was funded by public subscription. Originally there was an iron fence with small stone pillars at the corners all around the raised base, enclosing a water pump on the south side.

The sketch is based on a photograph taken in 1885 - by then the iron railings had gone and the pump at the back was out of use, though the very tall handle is still visible. Water was obtained by using the water key and hosepipe, shown on the right of the drawing. Public opinion grew that this monument was no longer appropriate for such a prominent site in a thriving town.

Where is the Obelisk now?

The Obelisk was moved to the corner of Speen Lane in 1888, after foundations for the new Jubilee Clock were dug at a ceremony attended by the Mayor and dignitaries of Newbury. An anonymous poem ‘In Memoriam of the Speenhamland Lamp’ was printed in the Newbury Weekly News of 15th November 1888.

For the next 100 years, the Obelisk stood neglected. As time passed its history was forgotten. Then, over a century later, Speen residents chose to restore it to a working streetlight for the Village Millennium Project, which included landscaping around the site. On the eve of 2000 the new light was ceremoniously switched on, during which a new poem about the Obelisk was recited and a new song about the history of the Obelisk was sung by all. So the Speenhamland Lamp lives on!

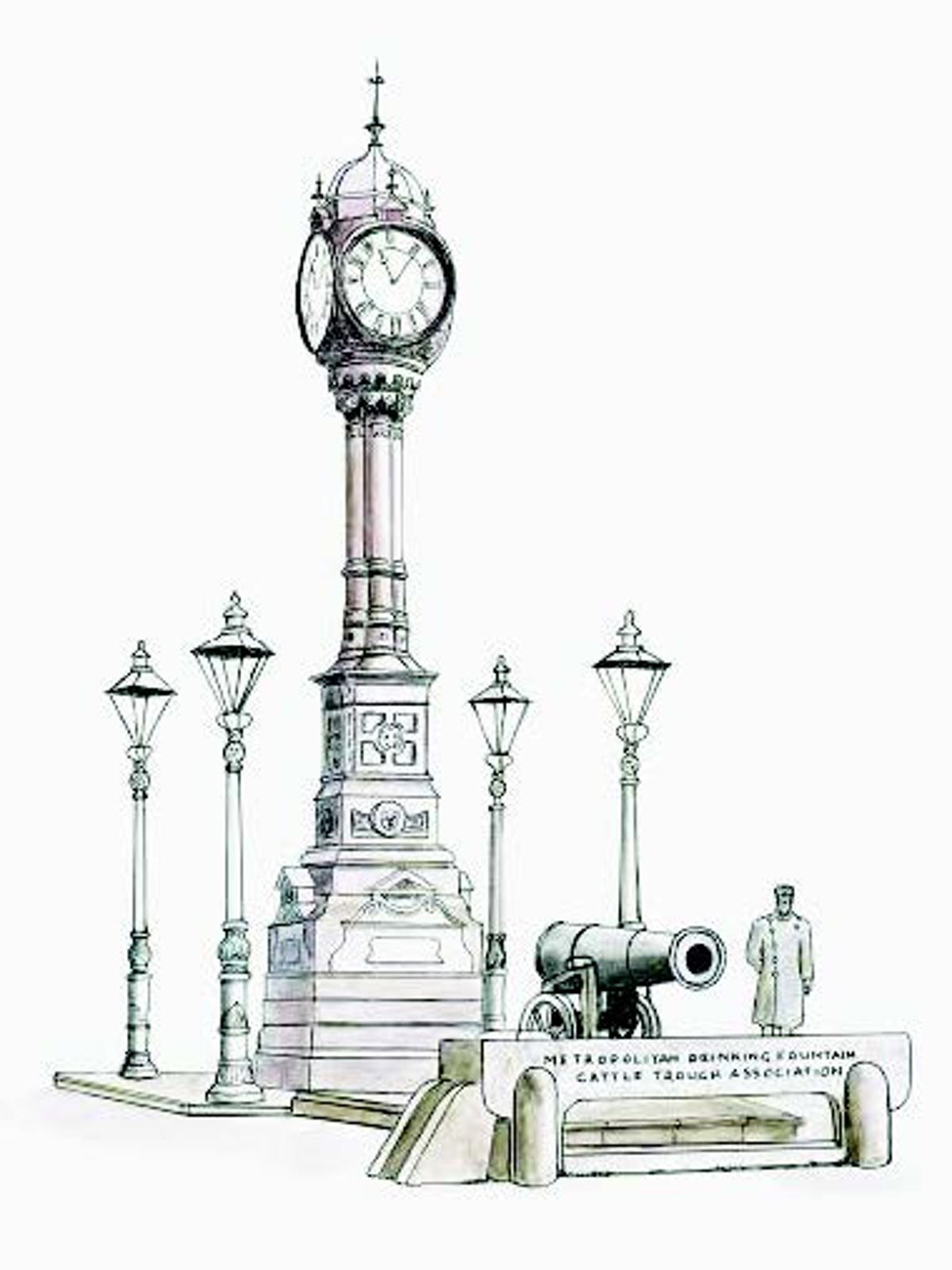

The Jubilee Clock 1889 - 1929

With Newbury’s growth in the 19th century, it was felt appropriate to celebrate 50 years of Queen Victoria’s reign in June 1887 by a new and more elaborate monument - an ornate iron clock with four faces, illuminated from below by four branching gas lanterns. Foundations were dug in November 1888 and the Jubilee Clock erected the following year, where it stood for 40 years.

The iron work was cast by George Smith of Glasgow & London and decorated in gold and colours by Ravenor of Speenhamland. A Russian cannon gun, captured during the Crimean War, stared down Northbrook Street, a reminder of the power of the British Empire.

The branching lanterns were soon replaced by four free-standing street gas lights; a cattle trough appeared in 1908, one of many troughs supplied by the Metropolitan and Drinking Fountain Association in the UK. Later additional ‘street furniture’ appeared – chain linked bollards on the corners and a traditional red public telephone box.

By the mid-1920s, when motor cars were beginning to be common, the Clock area had become an awkward and unplanned traffic ‘roundabout’, and the Victorian style was considered out of date. The presence of cars made access to the cattle trough and telephone box increasingly unsafe as well.

The Clock House 1929 to present

The present-day Clock House (or Clock Tower as it is also known) was designed by architect C.R. Rowland Clark and was the gift of James-Henry Godding. It was built as a little house with six sides, two of which have windows and another a door connecting to stairs leading up to the new clock. Originally the Clock House held a public telephone as well as providing sheltered seating. On the triangular turret, above the three clock faces, are depictions of previous structures on this site. Although it no longer has a telephone inside, it has remained an important and popular landmark in the town, set off by its own Christmas lights each year. It was a traffic roundabout until 2009, when the area on the east side was paved and pedestrianised.

Speenhamland and The Coaching Trade

From the 1780s until the arrival of the railways in the 1840s, Speenhamland was a very busy coaching stop on the two day journey between London and Bath. Only the wealthy could afford to travel, so they expected comfortable accommodation, good food and drink and some entertainment. In the Broadway they could choose between several inns - including The Chequers and The Bacon Arms – still here today. There was a popular theatre nearby to entertain them in the evening.

The most famous inn was The George & Pelican. Admiral Lord Nelson often stayed here on his way from London to visit his father in Bath. The George & Pelican included today’s Thames Court (behind you) and east as far as the courtyard we can see today. This was originally the entrance to a huge stable complex, which could house 300 horses. A horse pulling a passenger coach needed changing every 15 miles.

Quin’s witty lines are remembered:

“The famous inn at Speenhamland

Which stands upon the hill

Might well be called ‘The Pelican’

From its enormous bill”

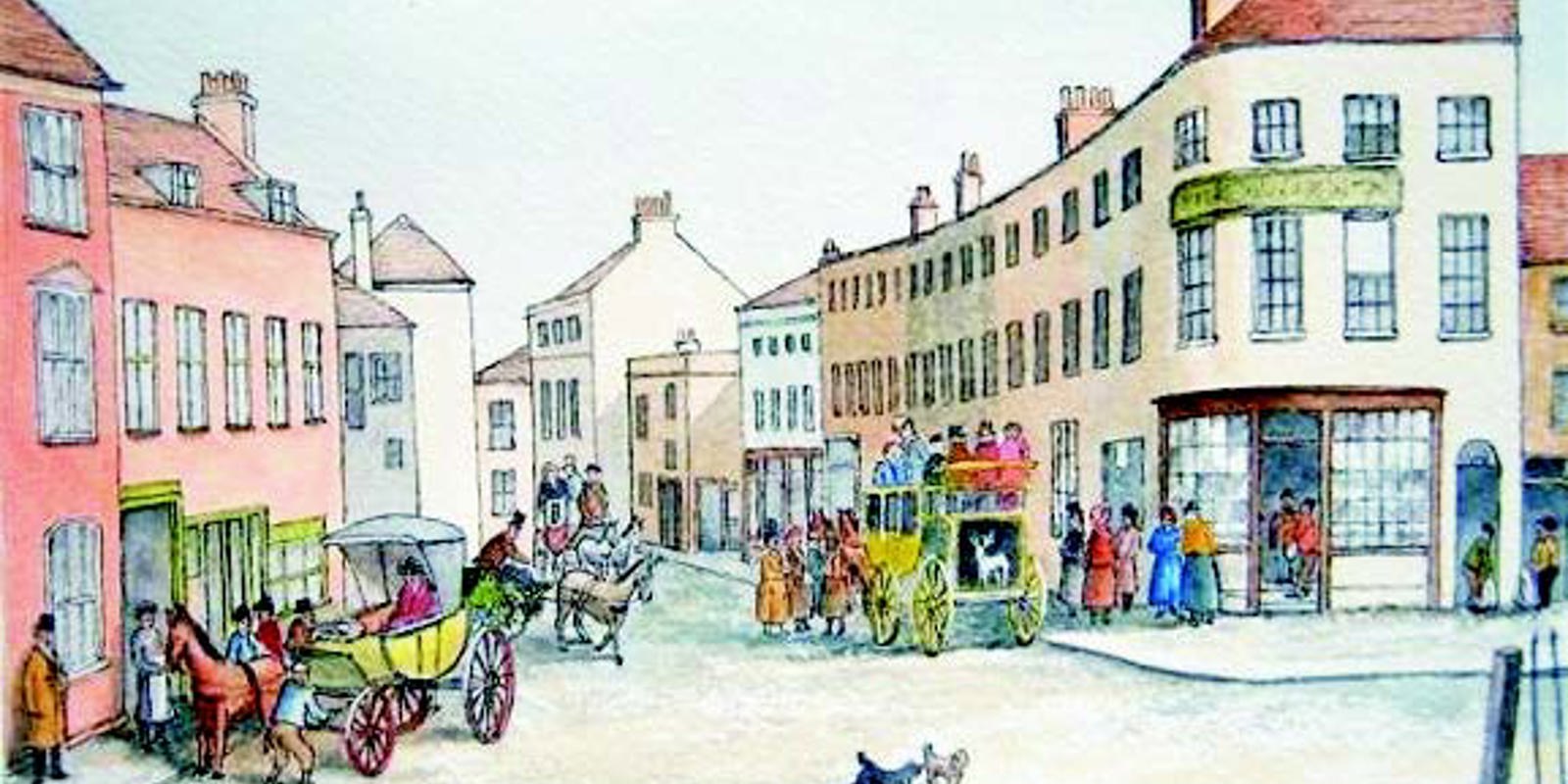

Newbury artist John Osgood (1811 – 1903) captured the busy character of the Broadway in the heyday of the coaching trade in a charming painting, now lost. Fortunately a print in a 19th century local history book survived and Newbury Town Council commissioned the above line and wash drawing by local artist Len Webb.

Interpretation

In the drawing above, several coaches can be seen in the Broadway, with the famous George & Pelican Inn on the left of the scene. Part of the iron fence surrounding the Speenhamland Lamp is just visible on the right.

In the original oil painting, Osgood created portraits of 15 local people, including 3 characters associated with the Pelican Inn - Mrs Botham, the landlady of the establishment, Jennings, the popular old waiter, and Jack Ashton, stud groom. There are portraits of three local coachmen, as well as a young Frenchman – a pupil at Osgood’s studio on The Bridge, where he lived with his family for 50 years.

The White Hart Day Coach, immortalised in the Pickwick Papers, can be seen on the right – the sign of the White Hart Inn is still visible on the north-east corner of the Market Place. Interpretation

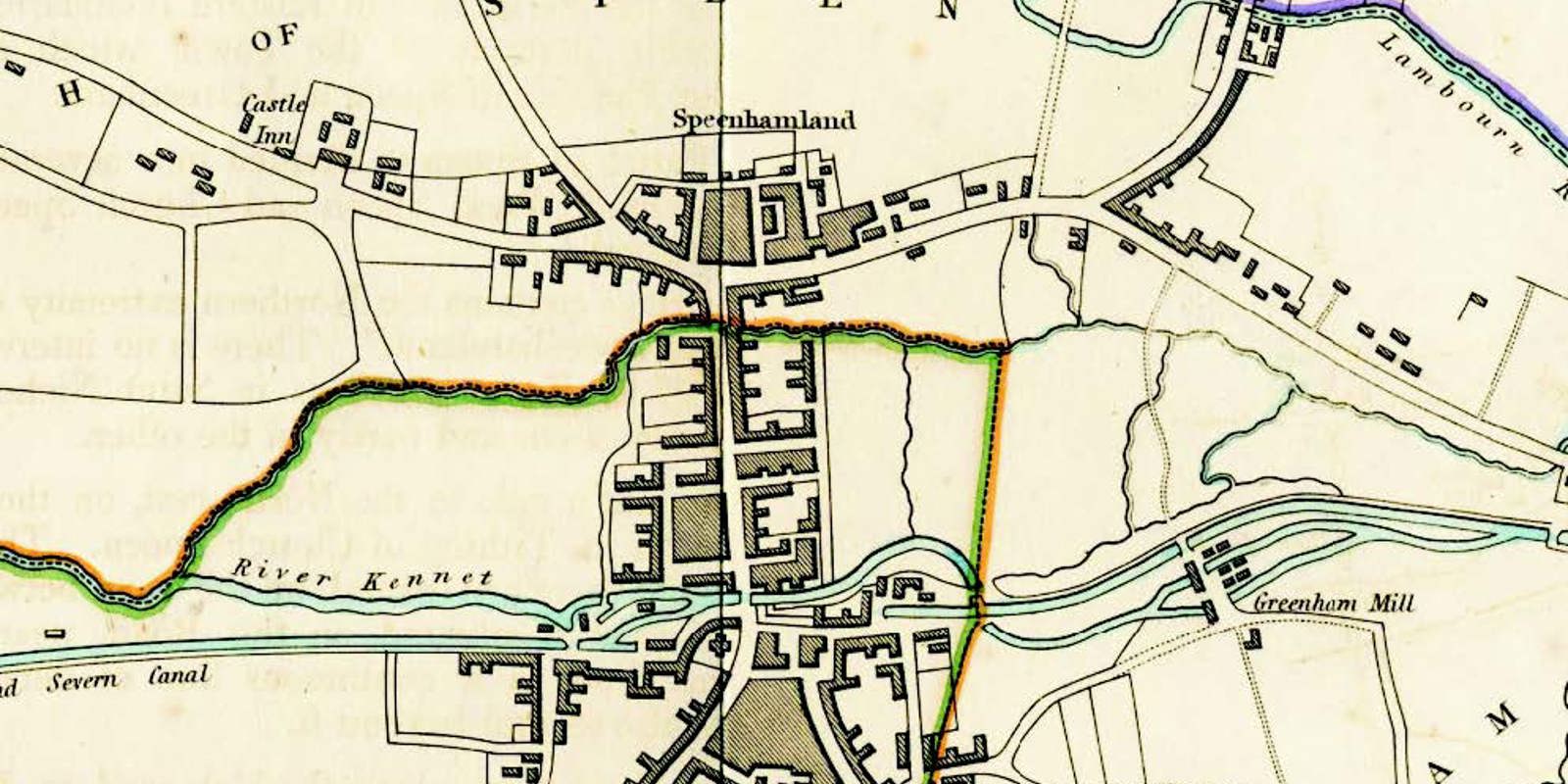

The History of Speenhamland

Until 1878 the Broadway area was in the Parish of Speen. The boundary was a stream, called Speenhamland Water or the North Brook. This was diverted under Northbrook Street by an underground culvert– the original stream bed can still be seen in the ditch at the bottom of Goldwell Park, which often fills up with rainwater. The line of the old Newbury/Speen boundary is marked on the map in green/orange and can be seen today as a line of bricks in the surface of Northbrook Street.

The Speenhamland System

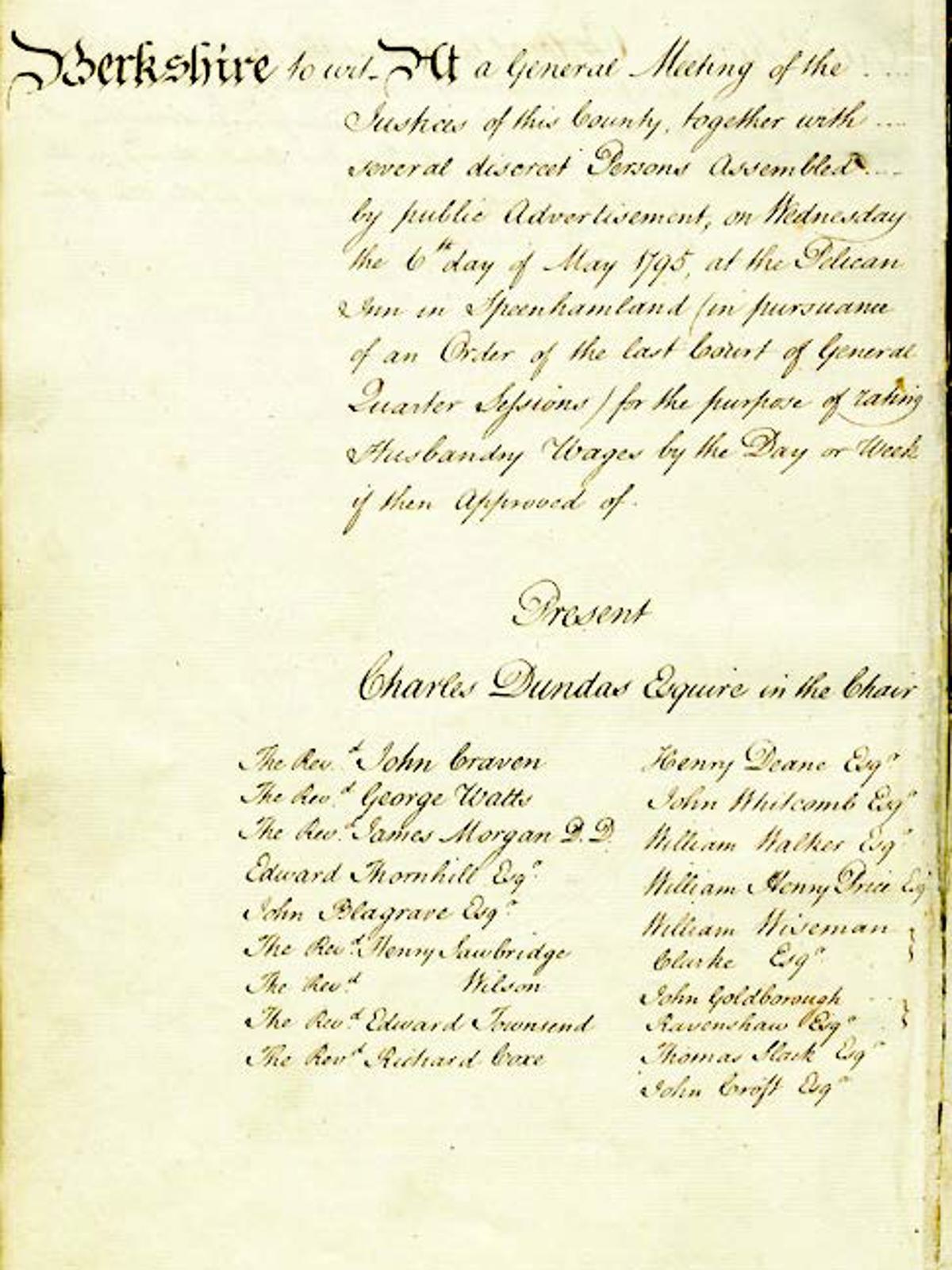

On 6th May 1795 the Berkshire Court of Quarter Sessions met at the Pelican Inn in Newbury, to discuss the situation of local agricultural workers. Land Enclosure had caused a fall in living standards: bad harvests sent food prices rocketing and the Napoleonic Wars with France (1793-1815) prevented grain imports. Labourers were poor and hungry. The Court feared riots and possible revolution if nothing was done to help.

Their answer was the Speenhamland System, an updating of the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. Parish rates (a levy on landowners) were to be used to ‘top up’ workers’ wages to a level linked to the cost of bread and the number of children in each family. Relief was based on the cost of a gallon of bread which weighed about 8lb 11oz or nearly 4kg. 3-gallon loaves were costed per working man and 1.5 per woman and 1.5 per child.

So, a man and wife with three children would be allowed the cost of 9 loaves per week. If a man’s wage was less than the cost of the bread for his family, the Parish rates would make up the difference. So as the cost of bread rose and fell, so would the relief from the parish.

The Speenhamland System was widely adopted across the south of England and was in use until the Poor Law Amendment of 1834. So, a man and wife with three children would be allowed the cost of 9 loaves per week. If a man’s wage was less than the cost of the bread for his family, the Parish rates would make up the difference. So as the cost of bread rose and fell, so would the relief from the parish.